Emotional intelligence is more than the ability to understand other people’s emotions. It starts with understanding the difference between emotions and feelings, which allows you to experience authenticity. As well as understanding that how you feel is not who you are. On the contrary, other people should influence your identity.

Did you know that there is a hugely significant difference between emotions & feelings? And that difference is the solution for many psychological obstacles you might face. More so, it allows you to experience authenticity and create a self-determined identity.

Managing your relationships and role expectations is one of the biggest obstacles you deal with daily. Since childhood, you learn to adapt your behavior, feelings, and thoughts according to social expectations. This is a big part of building a functioning society and how you learn to differentiate between ethical and unethical behavior.

But in that same process, you are also taught specific belief systems that are based on systems and structures that

- are not necessarily aligned with your own basic emotional understanding and

- might have been based on the traumatic memories of others – memories that you were never a part of in the first place.

This, combined with the lack of emotional education, often creates emotional confusion, stress, and anxiety. So what can you do to develop an emotional understanding that benefits you and your relationships?

Table of contents

The confusion behind emotions and feelings.

As stated by Elaine Fox (2018) and others, research on emotions has been inhibited because different phenomena such as feelings, sensations, mood, emotions, and similar are often studied under the same linguistic framework.

As Fox states, there have been numerous attempts to establish an agreed definition, but somehow academia has failed to do so. And even during my Ph.D. work, I chose the easier route of stating that there is a difference, but for simplicity’s purpose, I will focus on the term emotions.

But just like Elaine Fox, I have found that, generally, it is possible to create a distinction between emotions and feelings. Mainly because there is some degree across the faculties on how to separate the term affect (German Affekt; do create an effect in someone).

In some languages, it is easier than in English, which is why I refer in my work to other languages. Furthermore, I came to the conclusion that an interdisciplinary approach is what is needed to bring some light to the terminological confusion. An overarching approach is what can help us understand how emotions function not only with an individual but also within the context of society.

In the following paragraphs, I will unpack some of this confusion for you and create a workable definition of emotions and feelings. These definitions are based on research for my Ph.D.: ‘I feel, but I am not allowed to, so I don’t! The Story of Emotions and Masculinity in South African Prison.’ As well as my continuous efforts to create functional clarity.

For my research, I took a deep dive into the different definitions within social sciences, starting with sociology and psychology and then moving into social psychology and neuroscience.

Let’s start with a workable definition of emotions.

This is truly my favorite part of this topic. Especially after I came across the different definitions of emotion, I felt incredibly excited. And I hope that you will share the excitement with me.

Emotion in Latin means motus, which can be translated as to stir up, having been moved, in motion, as well as energy in motion. And energy isn’t bad or good. On the contrary, energy simply means that something is moving. In physics, we refer to the positive and negative poles between which energy is created. Again, though, there is no judgemental reference in this: no good or bad. Further, in Latin, emotions are also described as ‘motus anima’ meaning ‘the spirit that moves us‘ (Cherniss, 2000).

What are emotions?

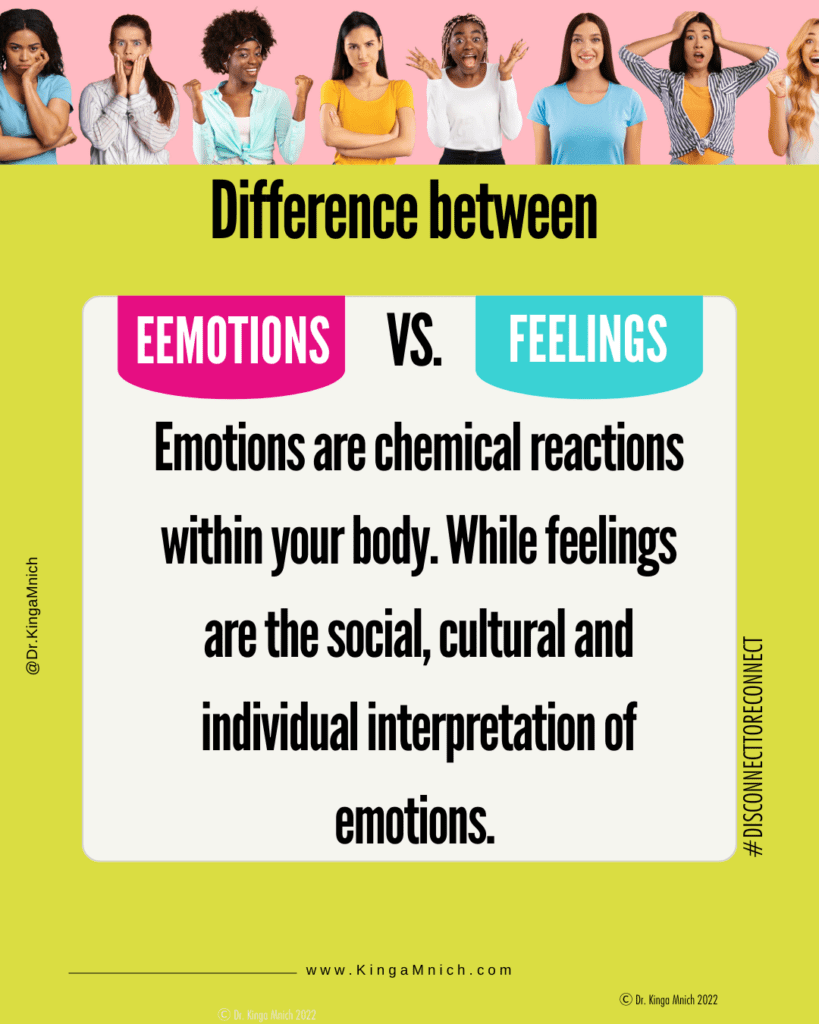

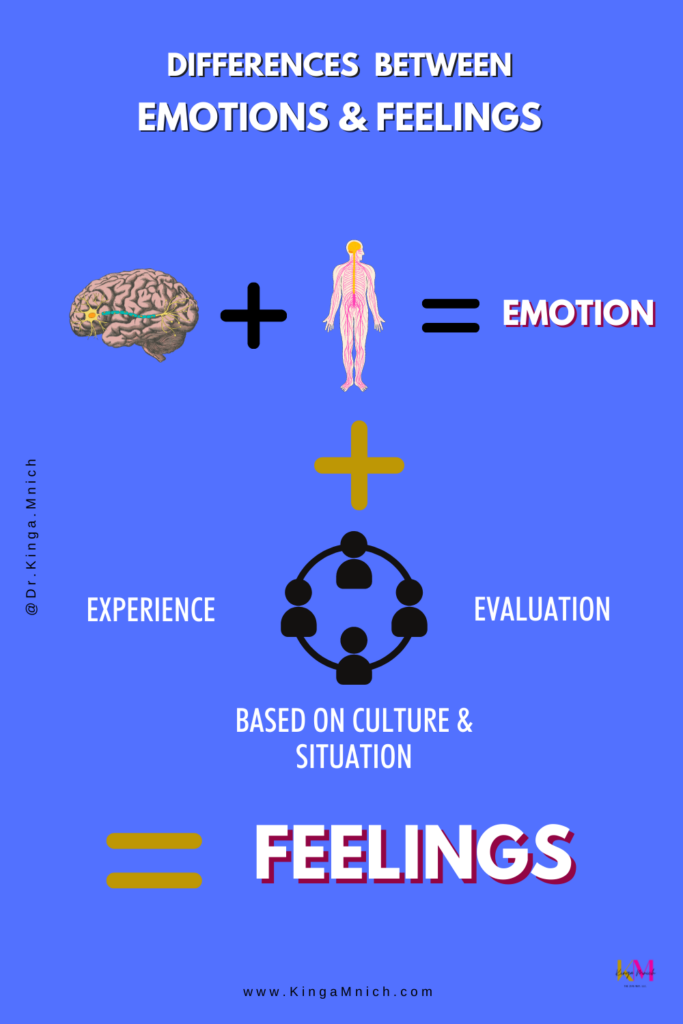

Emotions are chemical reactions. They are energy moving through your body and are part of what it means to have a human experience. Erving Goffman already proclaimed in his book ‘The presentation of self in everyday life’ that ” it is impossible not to interact with other people”. That is why it is impossible not to have emotions because emotions are part of every interaction we have.

On contrary to general psychology, which labels emotions and feelings as good or bad, I am proposing the detachment of labels. Unfortunately, you have most likely developed the habit of classifying the many different emotions you experience daily as either positive or negative instead of seeing them for what they are: energy in motion.

So let’s use energy in motion as the first part of our definition of emotions.

The second component of emotions.

Humans have one thing in common: we tend to overcomplicate things, especially regarding our well-being. This can be observed in two ways: 1. You might perceive your feelings as facts, and 2. Understand your emotions as feelings because you feel the sensation in you. You can certainly feel your emotions, but what you understand under ‘the feeling’ is not necessarily what you feel. A ‘feeling’ is the socialized and processed classification of your experience within an interaction.

Emotion + Socialization = Feeling

K. Mnich

What are feelings?

Feelings are the interpretation of what we are experiencing based on our social and cultural upbringing and our individual experiences and memories.

Let me summarize this: Emotions are chemical reactions within your body. At the same time, feelings are your personal interpretation of that reaction based on your individual social, cultural, and circumstantial experiences. Emotions are happening within you; they are raw signals guiding you. Feelings are your personally filtered version of those emotions.

Unfortunately, all too often, the filtered version doesn’t represent what you genuinely feel but what you believe you are supposed to feel. Feelings are, thus, often much more complicated than emotions – and have several layers of socially constructed (and misconstructed!) concepts.

Let me give an example:

Say a friend stood you up at a restaurant, and the next time you see each other, they don’t mention it, no apology, just lots of inconsequential small talk. You don’t bring it up either because you are surprised and confused by it not being mentioned. Then, when you arrive home, you tell your partner how disappointed and sad you are about this whole thing. But, underneath your calmness, aren’t you, in reality, at least a little angry about someone not respecting your time?

Anger is also a great example of how cultural factors have managed to firstly label an emotion and then insert an entire sub-system of rules/interpretations on how to suppress, change and rename it. All this for something as simple as feeling angry because someone has stepped over your boundary!

But healthy anger means that you understand where you stand on this particular matter. It also means that you are able to express authenticity.

Here is another example:

You gave an incredible presentation in front of the entire company. But your boss comes to you and criticizes that one typo on slide 44. Your boss has a history of undermining confidence and isn’t particularly known for supporting others in their career development. Nevertheless, instead of setting a boundary and standing up for yourself, you are ashamed and feel like a fool. How could that have happened?

Shame is a construct that has been used throughout history as a tool to align people to social and cultural norms. It is anchored within you as part of the identity you are supposed to represent. As a human being, you are rewarded through positive ones and ‘punished’ through negative impulses in interactions. Negative impulses are supposed to align you with social norms. Unfortunately, some people abuse emotions to impact you negatively and make you feel ashamed negatively.

Next time your boss shames you for an irrelevant mistake, remind yourself of his limitations. And remember that some people are not even aware of their words’ effect on you. Further, at the same time, redirect your thoughts to the positive feedback received from others.

Then, instead of questioning your own abilities, you will be addressing the real issues at hand and starting to set boundaries.

Understanding the difference between emotions and feelings.

The example of “Emotional Labor” and your feelings.

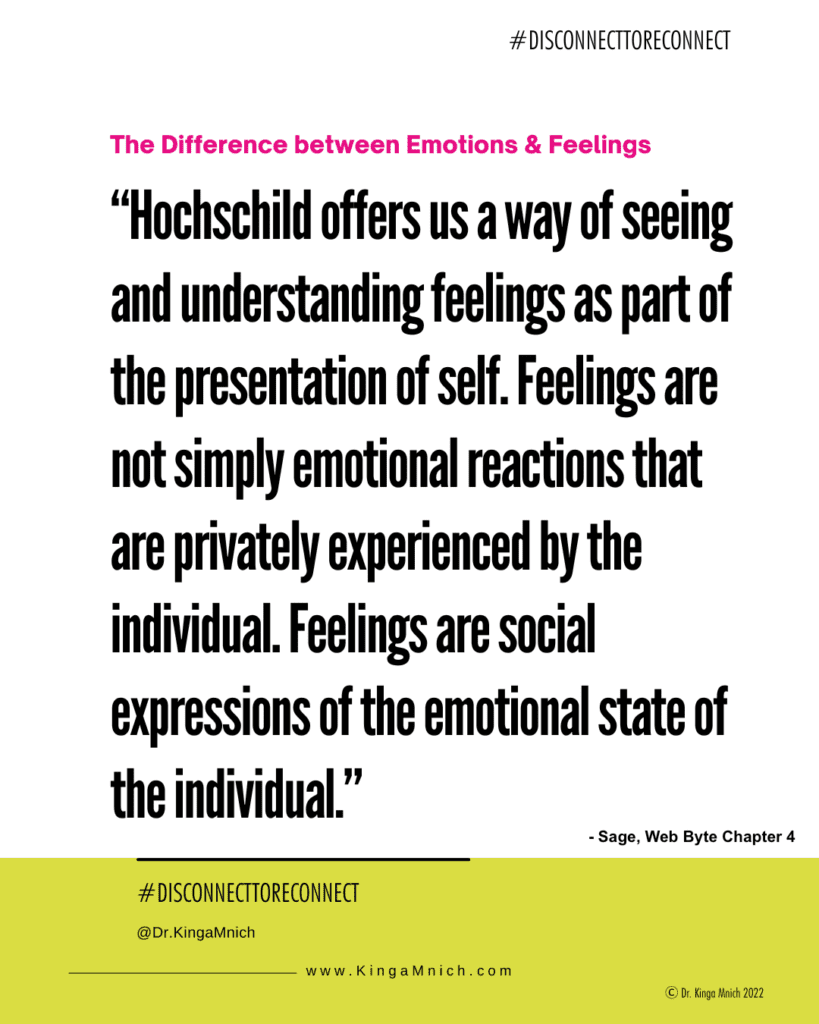

The difference between emotions and feelings becomes visible when we do emotional labor: a term that Arlie Hochschild coined in the 70s. It describes the act of aligning your emotional expression to socially expected feelings. Hochschild conducted her research predominantly by observing flight attendants adjusting their emotional expressions to standards of what the airline expects regarding how to treat customers even in difficult situations. In most cases, the feelings attendants experienced did not represent their own inner emotional world.

A great example is the difference between a fake and a real smile. What Hochschild started observing, and what many more described later on, is that the outside expectations eventually become the inner understanding of yourself.

The result is anxiety, depression, identity conflict, and even identity loss. You just don’t feel true to yourself.

I hope that, at this point, the difference between emotions and feelings is crystallizing. While emotions are internal directional and personal signals, feelings connect to your environment and cultural expectations. They are closely related and interconnected because they are sensations. Feelings can be changed and override emotions, which are chemical reactions to the outside world (see graphic).

You are experiencing emotions within you, whereas feelings are culturally constructed outside of you. Even though they have become a part of you, it is usually easier to name your feelings than your emotions. This is because, quite often, emotions are cluttered with feelings. Feelings give you a sense of who you are through the connection between your inner and outer world. That’s why many people believe that their feelings determine who they are, while their emotions are directions and energy.

So what does it mean to be yourself? Or to be yourself authentically?

Authenticity

This is how emotional awareness allows you to experience authenticity.

Why am I bringing up authenticity? Well, let me ask you this question: how often do you judge yourself based on how you feel?

What I mean is, how often do you believe that you succeeded in something because you felt good about yourself at the time? Or how often do you think less of yourself because you were not feeling well because someone else’s simple reaction was enough to shake your confidence again?

Authenticity involves both knowing who you are and showing who you are.

Knowing yourself means understanding your character, your interaction & communication style, and what you like and don’t like. It also means that you know what you stand for and your values. Knowing who you are, also means understanding your thoughts, feelings, and desires. Usually, you feel inauthentic when your words and actions (showing) don’t line up with your emotions (knowing) and when your actions don’t represent (showing) your thoughts and beliefs (your value system – knowing).

Although emotions and feelings happen instantaneously, learning to break down these processes will make it easier to discover authenticity and feel like yourself.

This is how you know that you are on the path of creating authenticity.

By going through this process and discovering authenticity for yourself, you will find yourself start making statements like this:

- I know who I really am.

- People have expectations, but they no longer impact me or my decisions.

- Pleasing people is no longer a problem. If they don’t like me they don’t need to be around me.

- I connect easily with new people.

- I am simply who I am.

Because identity and authenticity are so closely connected to how you feel in relation to the people around you, it can be challenging to understand who you are. The first step in achieving that understanding is gaining insight into your emotions. This insight enables you to create guidelines that [a] help you know what is going on within you personally and then [b] help you differentiate that from your perception of what others believe is going on – or should be going on – for you.

In other words, learning to understand the factors which change our emotions into our feelings is a strong starting point in understanding what you want out of life and how a few small changes in approach may yield rather special results!

Curious to learn more about emotions? Read here:

The Individualization Of Emotions

Emotion Theory and Research: Highlights, Unanswered Questions, and Emerging Issues

Reference List:

Barbalet, JM. 1998. Emotion, Social Theory, and Social Structure: A Macrosociological Approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Pres

Bolte Taylor, Jill 2021: Whole Brain Living: The Anatomy of Choice and the Four Characters That Drive our Life.

90sec: “When a person has a reaction to something in their environment, there’s a 90 second chemical process that happens in the body; after that, any remaining emotional response is just the person choosing to stay in that emotional loop”

Collins, Randall 1990. Stratification, Emotional Energy, and the Transient Emotions. In: Research Agendas: In the Sociology of Emotions. Albany: State University of New York

Dawson, Jow 2018: Emotions in Context: What We Know About How We Feel. Html: https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/emotions-in-context-what-we-know-about-how-we-feel 03/07/2022

E

Ekman, Paul 1992: An Argument for Basic Emotions. In: Cognition and Emotion 6: 169-200.

Ekman, P. 2016. What Scientists Who Study Emotion Agree About. In: Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(1), 31-34

Ekman, P. 1999. Basic Emotions. In Dalgleish, T. & Power, M. J. (Eds.), Handbook of Cognition and Emotion (pp. 45-60). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Ekman, P. 1999. Facial Expressions. In Dalgleish, T. & Power, M. J. (Eds.), The Handbook of Cognition and Emotion (pp. 301-320). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Ltd

F

Feldman Barrett, Lisa 2004. Feelings or Words? Understanding the Content in Self-Report Ratings of Experienced Emotion J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004 Aug; 87(2): 266–281. Html: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1351136/ accessed: 07.08.2018

Feldman Barrett, Lisa 2017. The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization. In: Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1-23

Flam, Helena 1999. Soziologie der Emotionen heute in: Masse – Macht – Emotionen. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag GmbH.

Fox, Elaine 2018. Perspectives from affective science on understanding the nature of emotion. Brain and Neuroscience Advances Volume 2: 1–8

H

Hochschild, Arlie R. 1979. The Presentation of Emotion. SAGE

Hochschild, Arlie R. 1983/2003: The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human feelings. Berkeley: University of California Press

Hochschild, A. 1979: Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85, pp. 551-575.

L

Leavitt, John 1996. Meaning and Feeling in the Anthropology of Emotions. In: American Ethnologist, Vol. 23, No.3 (Aug., 1996=, pp. 514-539

Manstead, A. S. R., Frijda, N. H., & Fischer, A. (Eds.). 2004. Feelings and emotions: The Amsterdam symposium. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Peil T, Katherine 2014. Emotion: The self-regulatory Sense. In. Glob Adv Health Med. March 3(2): 80-108

S

Sacco, T., & Sacchetti, B. 2010. Role of secondary sensory cortices in emotional memory storage and retrieval in rats. Science, 329(5992), 649-656. doi: 10.1126/science.1183165

Simon, Robin, and Leda E. Nath. 2004. “Gender and Emotion in the United States: Do Men and Women Differ in Self-Reports of Feelings and Expressive Behaviors?” American Journal of Sociology 109: 1137-1176

Shweder, R. A. 2004. Deconstructing the emotions for the sake of comparative research. In A. S. R. Manstead, N. H. Frijda, & A. Fischer (Eds.), Feelings and emotions: The Amsterdam symposium (pp. 81–97). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Stets, Jonathan H. and Jan E. Stets 2006. Sociological Theories of Human Emotions. In: Annual Review of Sociology 32: 25-32.

Stets, Jan E. 2005: Examining Emotions in Identity Theory. In: Social Psychology Quarterly Vol. 68, No. 1: 36-74

Stets, J.E. & Turner, J.H. 2006. Handbook of Sociology of Emotions. New York: Springer

T

Turner, Jonathan H. & Stets, Jan E. 2005. The Sociology of Emotions. New York: Cambridge University Press

V

Vuilleumier, P. 2005. How brains beware: neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends in cognitive sciences, 9(12), 585-594. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.011